Writer, journalist, playwright and theatre critic, Solomonov was born in 1976 in Khabarovsk, Russia.

In 1993, he moved to Moscow to enroll at the Department of Theatre Studies at the Russian University of Theatre Arts in the program of highly regarded theatre critic Nataliya Krymova. Solomonov graduated five years later with a thesis entitled “Dostoevsky and Contemporary Theatre.”

Following graduation, he spent a year in Berlin studying German theatre. Upon his return to Moscow, Solomonov began his career as a theatre critic. Over a thousand of his reviews and columns, including interviews with prominent European and Russian theatre people, were published in the most influential Moscow periodicals (the magazines Theatre and Theatre Life, the newspapers Gazeta, Izvestiya and Vedomosti). Several years later he became The Chief Editor of the Culture section at The New Times magazine, as well as The Head of the Special Projects Department and Public Relations Service at the Culture TV channel.

In 2010, he left both of his jobs ‒ The New Times and the Culture TV channel ‒ to begin writing his first novel, A Theatrical Story, in India.

Set in present day Moscow in a leading theatre, Theatrical Story is a novel that reacts to the most painful and problematic facets of modern Russian reality, including overarching influence of the Orthodox Church, homophobia, and the eternal dependency of a “little man” from those in power. It presents a model of a society going through spiritual and ideological crisis. It reveals the political problems in modern Russian life, and for that reason, it is not officially supported by Russian cultural authorities and does not have any government financial aid. It is a significant point that acclaimed Russian stage directors and renowned actors have commented on the novel – e.g. the prominent figure in avant-garde theatre, stage director Kirill Serebrennikov, has highly recommended this book, “[it] will be of huge interest to a smart reader.”

Despite the gravity of the subject matter, the novel is written in a witty, accessible style and is populated by characters that appeal to a wide spectrum of readers.

The novel’s first edition was published in Russia in 2013 and became an instant sensation in Moscow’s intellectual circles, gathering endorsements from leading cultural figures and opinion makers. In the first week of the novel’s release, it appeared on the bestseller lists of Moscow Bookstore, the major bookstore of the Russian capital, and on OZON.ru, the Russian equivalent of Amazon. For three months, the novel remained one of the top ten most popular literary works written in Russian.

The second edition featuring a foreword written by the author Ludmila Ulitskaya, has retained a similar position.

The novel’s third and fourth printing were published in 2017 and 2019 consequently.

Forbes, Snob, The New Times (magazine) and German Die Tageszietung have written about the novel, assuming over a hundred reviews, news articles and interviews with the author in Russia and abroad. A Theatrical Story was granted an individual stand at the Moscow Fair of Intellectual Literature NON/FICTION 2013. The novel was successfully adapted by a Moscow theatre and has been playing with all shows sold out.

Reporter and theatre critic Katja Kollmann with Die Tageszietung wrote: “A Theatrical Story is a true modern novel that plays out the eternal themes in the context of the modern society. A Theatrical Story is also contemporary from the point of view of literary studies. Having properly learned the lessons of postmodernism, the author takes a step forward: he brings the plot back to the center of the narrative and skillfully enriches it with theatrical, almost cinematic elements. Yet, the plot does not evolve just for the sake of the plot ‒ it serves the main ideas of the novel.”

Translation of the novel into English, German and Italian is currently being negotiated.

At the present moment, the author is working on a duology of this book, a novel that shows Russia in a slightly Orwellian future.

After finishing the novel, Solomonov penned the controversial political play «God’s Grace.» It was awarded by one of the main prizes at the 8th Biennale for Dramatic Art in London as the best political and social play, and was performed on March 7, 2019 in the Buinsk Drama Theater.

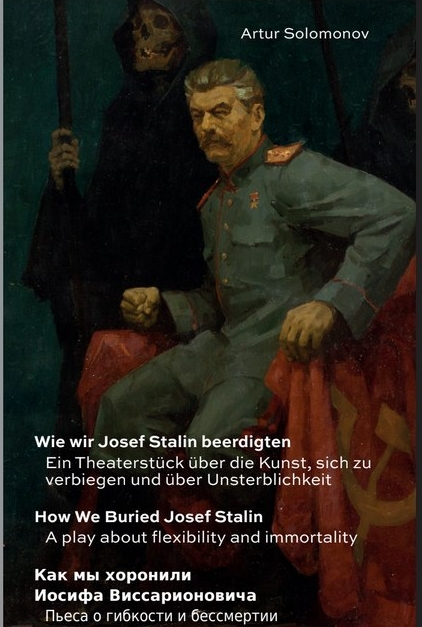

In January of 2019 Solomonov wrote his second play -«How We Buried Josef Stalin». The play — is a short and brilliant tragi-farce that takes place in a famous Russian theatre where the director is working on a play about Stalin’s death. (This then becomes the opposite — a play about Stalin’s birth due to political reasons and the presence of the Russian president who makes corrections to the Theatre Director that must be followed.)

The play received an overwhelming positive response from Russian theatre circles.

The Neue Zürcher Zeitung published an article about the event, and German Radio Deutschlandfunk opened their Daily News Release with the presentation of the play, as well as the interview with the author.

The play was published in The Snob Journal Online — on the 5th of March, the date of Stalin’s death. It turned out that the publication was quite a success — with more than 1000 shares during the first days after it was released.

On July 4, 2019 the premier of the stage reading was presented in Moscow Theatre Doc, with participation of the Russian film and theatre stars — Maksim Sukhanov and Julia Aug. The event was streaming live via MBK Media (Russian-language multimedia news platform owned by Mikhail Khodorkovsky, that covers regional news ignored by Kremlin-controlled media outlets) – with more than 40 000 views overall.

International theatrical festivals Kamerata (Cheliabinck 2019) and Evropeiskaya vesna (Archangelsk, 2020) included the play’s staged readings into agenda.

Famous Russian stage and film director Kirill Serebrennikov said about the play:

“Stalin’s funeral in our country, surprisingly, has not yet taken place. Therefore, the witty, well-constructed play by Arthur Solomonov, unfortunately, is still very relevant.

Although the story itself is about modern theatrical troupe that ventured into the burial of Stalinism and failed, it allows you to enjoy the carnival illusion of the possibility of such a funeral. By the way, the fact that Arthur has a keen knowledge of Russian repertoire theater makes it possible to experience the joy of recognition”.

“How we buried Josef Stalin” has been translated into English, German, Polish, Czech, Bulgarian, Romanian and Hebrew.

In September 2020 the tragifarce was published by the magazine Dialog (Dialogue), the only periodical in Poland, which regularly releases contemporary Polish and foreign plays, and by online magazine Asymptote (in English) — supported by London bookfair initiative for best word literature in translation.

In January 2021, in California, USA, Mary Ann Rodgers directed the first online production based on an English translation of the play.

On February 26, 2021, the opening night of the performance took place in Chelyabinsk. The production had a huge success and received an overwhelming Media response. The premiere was accompanied by the local Communist Party mass protests and solitary pickets to oppose the anti-stalinist performance of Solomonov’s play.

On January 2022 the play will be published in three languages as one book by the Austrian publishing house «Danzig & unfried».

DE. „Wie wir Josef Stalin beerdigten“

In einem ziemlich bekannten Theater entscheidet man sich, ein neues Stück über Stalin zur Uraufführung zu bringen. Die Rollen sind vergeben, das Bühnenbild steht und Pressevertreter sind zu einem Probenbesuch geladen. Unter den Probenbesuchern aber ist der russische Präsident. Süffisant erklärt er, dass es ihn wirklich sehr interessiere, wie sein Vorgänger auf der Bühne dargestellt werde. Artur Solomonows Stück handelt also von der Fähigkeit der menschlichen Psyche, sich zu (ver)biegen. Es beschreibt die Bereitschaft, unter gewissen Voraussetzungen die gefährlichen Praktiken einer totalitären Vergangenheit zu reproduzieren — Praktiken, die nie wirklich verschwanden. So hat im Grunde die Vergangenheit die Macht über die Gegenwart übernommen und macht sich daran, die Zukunft zu erobern. Das Stück zeigt, wie leicht jemand zum Tyrannen werden kann — und wie bereitwillig seine Umgebung ihm das zubilligt. Wir beobachten gebannt, wie stalinistische Praktiken sich auch heute in der menschlichen Psyche verfangen. Das Stück versucht sich an einer Erklärung dieses Phänomens und wirkt dabei furchteinflössend und komisch zugleich.

Artur Solomonow hat diese Tragikfarce im Jahr 2019 geschrieben. Veröffentlicht wurde sie erstmals auf dem Portal Snob.ru. Die Neue Züricher Zeitung und der Deutschlandfunk haben zeitnah darüber berichtet. Die erste öffentliche Lesung fand am 4.Juli 2019 im Moskauer Theater Teatr.doc statt — in den Hauptrollen die bekannten Schauspieler Maxim Suchanow und Julia Aug. Medial flankiert wurde die Lesung von den Zeitschriften Teatr, Sobesjednik, Teatral und einigen mehr. Auch die Radiosender Echo Moskvy und Svoboda ( Freiheit) berichteten daüber. Nicht wenige der führenden russischen Theater zeigten Interesse an dem Stück, aufgrund des politischen Klimas aber wagte sich kein Theater an eine Aufführung. Trotzdem fanden auf den internationalen Festivals „Kamerata“ in Tscheljabinsk (2019) und „Evropejskaja Wesna“ in Archangelsk (2020) szenische Lesungen statt.

Der berühmte Theater- und Filmregisseur Kirill Serebrennikow über das Stück: „In unserem Land ist Stalin — überraschenderweise — bis heute nicht beerdigt worden. Aus diesem Grund kommt dem witzigen, gut geschriebenen Stück von Artur Solomonow leider eine essenzielle Funktion zu. Obwohl die Geschichte von einem heutigen Theaterkollektiv handelt, das den Stalinismus beerdigen will und daran scheitert, gibt es trotzdem diesen Moment der Illusion, in dem diese Beerdigung Wirklichkeit werden könnte. Ein charmanter Nebeneffekt hängt mit Arturs profunder Kenntnis des russischen Repertoiretheaters zusammen: sie führt zu schönen Momenten des Wiedererkennens.“

„Wie wir Josef Stalin beerdigten“ wurde ins Englische, Polnische, Tschechische, Bulgarische, Hebräische und Deutsche übersetzt.

Im September 2020 wurde die Tragikfarce in der Zeitschrift „Dialog“, der einzigen polnischen Publikation, die sich der neuen polnischen und internationalen Dramatik widmet, veröffentlicht. Die englische Veröffentlichung (auf dem Portal „Asymptote“) wurde unterstützt von der London Bookfair Initiative für herausragende Weltliteratur in Übersetzung.

Im Januar 2021 hat Mary Ann Rogers in Kalifornien beim ersten Stream des Stücks — in englischer Übersetzung — Regie geführt.

Am 26.Februar 2021 fand in Tscheljabinsk die analoge Uraufführung statt. Die Inszenierung war ein großer Publikumserfolg und fand ein breites Medienecho. Eingerahmt wurde die Uraufführung von Protesten der örtlichen Kommunistischen Partei, welche die antistalinistische Haltung des Stücks scharf verurteilte.

Artur Solomonov, THEATRICAL STORY

Set in present day Moscow THEATRICAL STORY is a novel that reacts to the most painful and problematic facets of the modern Russian reality, including the overarching influence of the Orthodox Church, homophobia, and the eternal dependency of the “little man” from those in power.

It presents a model of a society going through spiritual and ideological crisis. Despite the gravity of the matter, the novel is written in a witty, accessible style and populated by characters that appeal to a wide spectrum of readers.

THEATRICAL STORY was published in Russia in 2013 and became an instant sensation in intellectual circles in Moscow, gathering endorsements from leading cultural figures and opinion makers. The novel was completely sold out and republished three times, and preparations for the fourth edition are now under way.

Synopsis

Present day Moscow. Sylvester Andreyev, а powerful, manipulative and authoritarian director of a famed Moscow theatre is planning a revolutionary production of Romeo and Juliet. This production will see the part of Juliet played by a man, and the part of Friar Laurence re-envisioned as a Buddhist monk, Brother Laurence. Both of these changes are certain to enrage the orthodox tastes of Russia’s political elite – in particular, Ippolit Karlovich, the oligarch who also happens to be the theatre’s biggest sponsor.

Alexander is the acting nobody selected to play the part of Juliet. Up until this point, Alexander has lived a melodramatic, miserable existence, blaming his unhappiness and inertia on the trauma of discovering his mother had considered having an abortion when she found out she was expecting him. Alexander is also tormented by the fame of the brilliant star of his acting company, Sergey Preobrazhensky, and nurses fantasies of killing him – until he learns that his nemesis is to play the Romeo to his Juliet. The part of Brother Laurence is given to Ganel, a dwarf who has been plucked from obscurity playing elves and dinosaurs at a local children’s theatre.

Alexander’s change of career coincides with the restyling of his personal life. He meets Natasha, a would-be actress whose biggest acting role came playing Juliet in her high-school play, and who now fritters away her time in fiasco auditions and fleeting romances. Natasha is married, but she and Alexander begin a passionate affair, and Alexander oscillates between bouts of jealousy and gratitude at their relationship.

Rehearsals begin, and Alexander literally immerses himself into the life of the thirteen-year-old character of Juliet. He can no longer tell stage from real life, and he finds himself being drawn to Sergey, who is increasingly perturbed by his attentions. Alexander assures Natasha that his infatuation with Sergey is no more than stage-induced and, to prove his abiding affection for her, he persuades Sylvester to offer her a job. By this point, Natasha has left her husband, in the hope that her relationship with Alexander will give her a chance to improve her own acting career.

Joseph, a bitter journalist who has been tasked with updating the script of Romeo and Juliet for this production, tips off Ippolit Karlovich about Sylvester’s radical plans for the play. Joseph has hatched a plan to take over the theatre, and hopes that his denunciation will force Ippolit Karlovich to fire the bullish Sylvester for damaging his image (any self-respecting oligarch – especially a patron of the arts – must be the very model of godliness). Ippolit Karlovich doesn’t actually live a particularly devout life (for example, he “claims” the first night of each new production with the actress involved), but he understands that an outward adherence to Orthodoxy is an advantage in Russia’s new political landscape. His spiritual guide, Father Nikodim, is an Orthodox zealot who secretly dreams of bringing art to the service of religion, and he manipulates Ippolit Karlovich to this aim.

When Father Nikodim learns of Sylvester’s plans for the play, he manages to convince the oligarch of the “damage” this interpretation will do in the new Russian reality, and puts pressure on him to intervene. Alleging that turning a woman into a man as well as a Christian into a Buddhist are crimes against ethical and religious values, they demand that Sylvester revert to a traditional interpretation of the play. In defence of his artistic freedom, Sylvester begins to strike out against the oligarch and the priest, inadvertently causing havoc throughout the entire company, including between Natasha and Alexander. Sylvester organises a blasphemous stunt during one of Father Nikodim’s church services, and at the premiere of Romeo and Juliet he plans to present a farcical parody of the oligarch’s relationship with the priest. The cruelty of this battle, as senseless and bloody as the one in Shakespeare’s drama, forces Alexander and Natasha to re-evaluate their commitment.

To distract the oligarch from his religious path (thus reducing Father Nikodim’s influence on him), Sylvester decides to bring Natasha to Ippolit Karlovich’s attention. Although her acting is terrible, he gives her the role of Juliet and removes Alexander from the role. As is his custom, Ippolit Karlovich invites Natasha to his hotel. Natasha accepts the offer out of fear of being fired, and in the hope that the oligarch can enhance her career. This news spreads through the theatre like wildfire. Natasha’s infidelity ruins Alexander’s faith in true love, and leads to their breakup. This emotional upheaval forces Alexander to confront the “traumas” of his past, and he and his parents reconcile.

As the premiere approaches, Sylvester and Ippolit Karlovich’s ongoing tussle for power gets out of hand. In a final, desperate attempt to gain control, the oligarch picks a drastic, destructive course of action: he orders the death of Sergey Preobrazhensky, in a staged car crash.

Following Sergey’s murder, the theatre is shocked and united in grief, and the outraged Father Nikodim finds himself in a standoff between the oligarch and the theatre director. He is disgusted by the actions of both murderer and provocateur, but makes his decision in favour of Sylvester. At Sergey’s remembrance ceremony, held in his church, Father Nikodim publicly names the true murderer. Meanwhile, a shocked Silvester vows to take his revenge on the man who murdered his best actor, at any cost.

The director and the priest, once sworn enemies, now find themselves in the same position. Father Nikodim realises that his dream of an “Orthodox theatre” is impossible, and awaits the oligarch’s inevitable revenge. He acknowledges that his proximity to riches and power killed the priest he once was, and in the hope of finding his true path once again he leaves his church and Moscow. Sylvester, on the other hand, can no longer remain in Ippolit Karlovich’s theatre. He tells the company that he is leaving to seek out new theatrical forms and ideas as an independent artist.

Hoping to rid themselves of the “theatrical bacillus” that has thrown their lives and emotions into disarray, Alexander and Natasha decide to leave the theatre and try to start their relationship afresh.

From the reviews:

Typically, it is the literature that breast-feeds the theater. Quite rarely it is other way around. “Theatre” by Somerset Moem, “A Dead Man’s Memoir: A Theatrical Novel», “Steppenwolf” by Hermann Hesse are among the examples. “A Theatrical Story” by Arthur Solomonv falls in the league of these rarities.

Vladimir Mirzoev, stage director

Arthur Solomonov wrote a hilarious, angry and tender book about theatre, which he hates as only love can do. You won’t regret reading it!

Victor Shenderovich, writer

I know well Arthur Solomonv’s talent, precision and honest wit. I know what he stands for in this world, and I am sure that his first large novel combining mystery with theatrical drama and time chronicles will be of huge interest to a smart reader.

Kirill Serebrennikov, stage director

The literary critic Nikolay Aleksandrv (“The New Times” journal) called “A Theatrical Story” the brightest debut of the year.

In the first weeks after publication, this book was profusely covered in mass-media including TV-channels “Cultura” and «Live News», radio stations “Echo of Moscow” and “City-FM”, journals “The New Times”, “Teatral” and “Time-out”, on-line editorials in “Forbes-on-line”, “Private correspondent”, “Orthodoxy and the world”, ”Gay.ru” and others.

After the first week in stores, the book made to the bestsellers list of the “Moscow” bookstore, the most prominent one in the capital of Russia. From that point on it holds its leading position, among top 10 modern Russian books and among top 20 of combined sales of both, Russian and foreign authors.

IT + DE

Sergio Mazzanti – Docente di Lingua e traduzione russa (Università di Macerata), traduttore italo-russo

Sono spesso delle casualità che ti portano a leggere dei libri importanti: un favore all’amica di un’amica e ricevo in regalo Storia teatrale (in russo Teatral’naja istorija), romanzo del debuttante scrittore russo Artur Solomonov. Abituato alla grafomania della Russia di oggi, che ha un numero di scrittori di poco inferiore a quello dei lettori, mi accingo con un po’ di scetticismo alla lettura. Noto subito che lo stile, sebbene sottile e ricercato, è lontano dalla cripticità di molti scrittori contemporanei, figli dell’era postmoderna, in cui si coglie quel pizzico di presunzione che sembra dire: “lo scrittore sono io, sei tu, lettore, che ti devi sforzare di capirmi”. La lettura scorre piacevole e sempre più appassionante, non riesco a staccarmi dalla lettura e in 3-4 giorni finisco il non breve romanzo senza un attimo di noia. Ritrovo il gusto della lettura fine a se stessa, a cui anni di studi di critica letteraria mi avevano un po’ disabituato. Penso subito che il romanzo potrebbe piacere anche fuori dalla Russia, sorge il desiderio di tradurlo e da lì la conoscenza con l’autore. Nella prima parte del romanzo si ritrovano alcuni tra i temi ricorrenti nella letteratura di tutti i tempi, come l’insoddisfazione esistenziale di Aleksandr, giovane attore incompreso, o la delicata scelta se praticare o meno un aborto, fino al tema dostoevskiano della premeditazione di un delitto. Qui però il romanzo cambia: la linea dostoevskiana era forse solo un inganno letterario, cancellato dalla storia d’amore con Natasha, anche lei attrice di seconda categoria. Un “amore moderno”, in cui la passione sessuale e l’autoinganno si fondono con l’innamoramento. Sì, perché Storia teatrale è un autentico romanzo della contemporaneità, dove gli eterni temi della letteratura di tutti i tempi vengono reinterpretati attraverso la chiave della società di oggi. La società russa postsovietica, ovviamente, con i suoi onnipotenti oligarchi, le sue dicotomie tra grandezza e meschinità, la sua peculiare commistione di politica e religione (di forte impatto la figura del sacerdote ortodosso che vuole fondere teatro e missione); ma anche, più in generale, la società umana contemporanea, sempre più globalizzata e simile in tante parti del mondo, schiava del denaro e schiavizzatrice dell’uomo. Come evidente già dal titolo del romanzo, la linea narrativa principale è quella del teatro, dominato dalla figura del geniale e autoritario regista, da cui parte la scintilla principale della narrazione: in una nuova, rivoluzionaria messa in scena di Shakespeare ad Aleksandr viene assegnata la parte di… Giulietta! (a corollario, il monaco Lorenzo viene trasformato in un monaco buddista e interpretato da un nano). Il tema del travestimento teatrale si mescola inevitabilmente, ma con delicatezza, con quello gender, argomento particolarmente delicato in una Russia alquanto omofobica. Ma più in generale la realtà teatrale in Artur Solomonov interagisce continuamente con la “realtà reale”, di cui rappresenta in un certo senso l’alter ego: amore nel teatro e amore nella vita, successo nel teatro e successo nella vita, etica nel teatro e etica nella vita, in una continua tensione che svela tanti aspetti dell’una e dell’altra realtà. Dopo una sequela incalzante di colpi di scena, tradimenti, innamoramenti eterosessuali e non, prostituzioni e omicidi, Aleksandr e Natasha riescono comunque a trovare le forze per andare avanti. Ed è qui, quando comincia la vita, che termina il romanzo, lasciando nel lettore un lieve sapore di lieto fine, ancor più piacevole proprio perché inaspettato… Storia teatrale è contemporaneo anche dal punto di vista letterario. Senza dimenticare la lezione del postmodernismo, rappresenta un passo avanti, in particolare con il ritorno alla centralità della trama, orchestrata sapientemente da Solomonov con elementi teatrali, se non cinematografici, ma mai fine a se stessa, sempre finalizzata alle idee che sono alla base del romanzo. Idee interessanti, complesse, nuove, che riflettono la novità e la complessità della società odierna. Una forma letteraria antica, il romanzo, rinnovata alla luce della letteratura precedente, per esprimere temi umani eterni, sulla base di una società specifica, quella russa, e attraverso di essa della società umana in generale.

Artur Solomonov. CV breve

Scrittore, giornalista, drammaturgo.

Nato nel 1976 a Khabarovsk da una famiglia dei professori.

Nel 1993 arriva a Mosca e dopo aver superato l’esame di lingua nipponica diventa studente dell’Istituto Statale d’arte teatrale (GITIS). Sceglielafacoltà diCriticaTeatraleacuradibrillante e finecritico e studioso di teatro, moglie del leggendario regista russo Anatoly Efros NataliaKrumova.

Tra cinque anni si laurea con la tesi “Dostoevskij e il teatro contemporaneo”.

Dopo la laurea abbandona la Russia e per un anno viaggia coll’autostop in Europa studiando teatro europeo.

Tornato a Mosca diventa nel giro di pochi anniautorevole ed abile critico di teatro. Pubblica più di mille recensioni sugli spettacoli ed interviste con personaggi di spicco di teatro russo ed europeo nei più importanti quotidiani e riviste (riviste “Teatro” e “Vita teatrale”, quotidiani “Gazzetta”, “Izvestia”, “Vedomosti”). Qualche annodopo diventa redattore della rivista The New Times e capo dell’Ufficio stampa del canale TV Cultura.

Nel 2010 lascia tutti i due incarichi e va in India dove si mette a scrivere il suo primo romanzo “Storia teatrale”.

«Eine Theatergeschichte» — Resume (von Valeria Achmetjewa, Lektorin)

«Eine Theatergeschichte» von Artur Solomonow steht in der Tradition des russischen realistischen Romans im Stile Fjodor Dostojewskijs. Dieser Roman vereint psychologische Analyse, Satire und philosophische Betrachtung. Im Grunde bemüht sich der Roman um eine Annäherung an folgende Phänomene: die Schauspielkunst, den Schauspieler, das Theater und vor allem die Wechselbeziehung zwischen Theater und Realität. Aber auch die Kirche und seine Würdenträger spielen in diesem Roman eine wichtige Rolle. Theater und Kirche interagieren — und die Grenzen zwischen Theater und Kirche lösen sich auf.

Ort der Handlung ist ein großes Moskauer Theater. Der Autor muss die Moskauer Theaterkreise sehr gut kennen. So beschreibt er die Aufregungen der Schauspieler minutiös und analysiert detailliert das Phänomen der Verwandlung (Sehr beeindruckt hat mich die Textstelle, in welcher der Autor die Gedanken eines talentierten Schauspielers beschreibt, der zufällig einen Hund im Fenster sieht und sich überlegt, was dieser Hund an Emotionen in diesem Augenblick durchlebt und sich so beginnt, in diesem Hund zu «verwandeln».)

Der gegenwärtige Moskauer Theaterkosmos wird bei diesem Autor zur Satire. Diese aber ist nicht nur böse, denn immer wieder scheint das Mitgefühl mit den Schauspielern durch, die das Theater wirklich lieben und versuchen, dem Theater, so gut es geht, zu dienen.

Die Handlung des Romans konzentriert sich um Vorbereitung einer Neuinszenierung von «Romeo und Julia». Sascha, ein nicht besonders talentierter Schauspieler, ist der (Anti-)Held des Romans. Sascha fühlt sich von seinen Eltern nie wirklich angenommen (witzigerweise ist sein Vater Psychotherapeut). Als Schauspieler ist er erfolglos und hat eine Affäre mit der ebenfalls erfolglosen Schauspielerin Natascha, die wegen ihm ihren Mann verlässt. Plötzlich soll Sascha die Julia spielen. Sylvester Andreewitsch Andreew, der Regisseur, möchte Shakespeare abseits von den konventionellen Pfaden inszenieren. Julia soll so von einem Schauspieler dargestellt werden (der Regisseur ist aber eigentlich gegen Homosexualität), Bruder Lorenzo soll nun ein buddistischer Mönch werden. Außerdem sollen viele Szenen vom bekannten Theaterkritiker Jossif (Pseudonym «Jossif Flavin») in eine aktuelle Sprachform gebracht werden. Nachdem Sascha seinen innerlichen Widerstand (begleitet von Streitereien mit Natascha) überwunden hat, beginnt er die Julia zu proben und verliebt sich in den Schauspieler, der den Romeo spielt: Sergej Preobraschenskij, einen talentierten und sehr bekannten Schauspieler. Der Regisseur bekämpft Saschas Verliebtheit. So soll Sascha dieses Gefühl nur spielen, aber auf keinen Fall selbst durchleben. Für die Rolle des Lorenzo holt der Regisseur einen Schauspieler aus einem anderen Moskauer Theater (Theater des jungen Zuschauers), den Zwerg Ganel. Ganel durchlebt bald eine schreckliche Phase der Bewußtwerdung, als er sich vom Regisseur hintergangen fühlt.

Und so weiter…

Parallel zu dieser Hauptlinie des Romans entwickelt der Autor Nebenhandlungslinien. Die wichtigste konzentriert sich um den Konflikt zwischen dem Regisseur Sylvester Andreewitsch und Pater Nikodim, dem geistlichen Vater des orthodoxen Bankiers Ippolit Karlowitsch, der wiederum der Hauptsponsor des Theaters ist.

Pater Nikodim nutzt seinen großen Einfluß auf Ippolit Karlowitsch — um sich gegen Neuerungen im Theater auszusprechen, die er als gotteslästerlich empfindet. Überhaupt ist er einer der größten Feinde des Regisseurs und träumt davon, ihn von seinem Posten als Intendant zu stoßen. Bald wird klar, warum er Sylvester Andreewitsch weghaben will. Nikodim träumt von einem «orthodoxen Theater» mit ihm selbst an der Spitze. Sylvester wiederum möchte seine Inszenierung ohne Abstriche realisieren und gleichzeitig den Sponsor nicht verlieren.

Ein Krieg beginnt: alle Personen basteln an Intrigen (es beginnt Jossif, der Theaterkritiker — dem Autor gelingt hier ein sehr ambivalentes Bild), alle versuchen, andere Personen auf die eigene Seite zu ziehen, und alle nehmen immer wieder Einfluss auf den Bankier (der sich beim Beobachten ihrer Spielchen kräftig amüsiert). etc..

Als man als Leser zu der Überzeugung gelangt ist, dass das Theater den Kampf gegen die Kirche gewonnen hat, provoziert Ippolit Karlowitsch, der es nicht aushalten kann, wenn sich irgendetwas seinem Willen nicht unterordnet, einen Autounfall. Preobraschenskij kommt dabei zu Tode. Die Proben werden abgesetzt. Sylvester hat den Kampf verloren.

Bei der Beerdigung Preobraschenskijs treffen sich alle wichtigen Personen in der Kirche (Ippolit Sylvester verfolgt das Geschehen per Video) und der Konflikt kocht jetzt auf höchstem Niveau: Sylvester bereitet eine gezielte Provokation gegen Nikodim vor, aber Nikodim selbst hat nach einer schwierigen inneren Bewusstwerdung (vom Autor sehr gut beschrieben) begriffen, dass seine Idee eines «orthodoxen Theaters» nicht zu verwirklichen ist. Nebenbei denkt er darüber nach, ob Ippolit Karlowitsch den Tod des Schauspielers von langer Hand geplant hat.

Nikodim flieht aus Moskau, und ein neuer Tag beginnt.

Man liest diesen Roman in einem Zug, ist gefesselt. Die einzelnen Handlungsstränge entwickeln sich völlig überraschend und sehr dynamisch. Gleichzeitig ist das kein leichter Lesestoff: ein Kampf der Ideen findet statt, bei dessen Beschreibung sämtliche literarische Formen verwendet werden, die für den klassischen russischen Roman charakteristisch sind.

Den Roman ist außerdem eine schroffe (und sehr lustige) Satire des gegenwärtigen russischen Charakters an sich, besonders aber der heutigen russischen Bourgeoisie.

Die Elemente des fantastischen Realismus zeigen sich besonders in den Traumsequenzen und Fieberphantasien der Personen. Hier erinnert der Roman sehr stark an die Prosa Dostojewskijs.

Besonders gelungen sind dem Autor die Dialoge: sie sind genau, logisch und haben einen tollen Rhythmus.

Der Autor verwendet eine Literatursprache, die über einen sehr großen Wortschatz verfügt und immer den richtigen Ton trifft.

Meiner Meinung nach ist «Eine Theatergeschichte» ein Stück Prosa, das einen großen Leserkreis finden kann und mit Hilfe einer guten Werbestrategie zu einem kommerziellen Erfolg wird.

„Eine Theatergeschichte“ von Artur Solomonow

Nachfolgender Text ist auf der Rückseite des Buches, das am 7.9. 2013 auf russisch erschienen ist und sofort auf Platz der 14 der russischen Belletristik-Bestseller geklettert ist, abgedruckt .

Es ist der Traum eines erfolglosen Schauspielers, der seit Jahren an einem bekannten Theater angestellt ist, aber nur Nebenrollen bekommt: er soll Shakespeares berühmte Julia spielen. Das erste Mal wird er persönlich zum Intendanten gerufen. So beginnen die Abenteuer unseres Protagonisten. Abenteuer voll mit Humor und Traurigkeit. Abenteuer, in denen orthodoxe Priester und Regisseure, Journalisten und Künstler vorkommen, schönen Frauen auftreten, Oligarchen Einfluss nehmen wollen und gewisse Katzen eine wichtige Rolle spielen.

Die turbulenten Ereignisse finden in einem sehr bekannten Moskauer Theater und einer orthodoxen Kirche statt. Von diesen beiden Orten wird auch der Kampf um die Gunst des Publikums geführt. In In diesem Roman spiegelt die lächerliche und tragische Welt des Theaters die gegenwärtige russische Gesellschaft. Die Künstler umgibt falscher Ruhm, verbunden mit dem Zwang zur sogenannten Selbstverwirklichung. Die Journalisten wollen alles herausfinden, nur nicht die Wahrheit. Der kirchliche Würdenträger schmiedet Intrigen und geht eine Allianz ein mit den Starken der Welt … Aber im Theater brennen noch ganz andere Leidenschaften: die unvorhersehbare und mit viel Dramatik aufgeladene Geschichte einer Liebe.

Der Roman sticht den Finger in die aktuellen Wunden der russischen Gesellschaft: thematisiert werden der wachsende Einfluss der orthodoxen Kirche auf die Gesellschaft, das Ausleben der Homosexualität in einem Land, in dem das faktisch verboten ist, und die Abhängigkeit des „kleinen Mannes“ von allen, die an der Macht teilhaben und deswegen für ihn Stärke symbolisieren.

„Eine Theatergeschichte“ vereint mutige soziale Satire, psychologische Analyse, grellen Humor und ein fesselndes Sujet. Ein Roman, den man erst aus der Hand legt, wenn man den letzten Satz gelesen hat.

Meist ist es so, dass die Literatur das Theater nährt – so wie die Mutter ihr Kind. Sehr selten geschieht das Gegenteil. So in „Theater“ von Somerset Maugham, im „Theaterroman“ von Michail Bulgakow und in Hesses „Steppenwolf“. Der Roman „Eine Theatergeschichte“ setzt die Reihe dieser Ausnahmeromane würdig fort.

Wladimir Mirosew, Regisseur

Artur Solomonow hat einen lustigen, bösen und zugleich zärtlichen Roman über das Theater geschrieben. Er hasst das Theater mit solch einer Intensität, zu der wiederum nur jemand imstande ist, der liebt.

Viktor Schenderowitsch, Schriftsteller

Ich kenne diesen talentierten, genauen und aufrichtigen Artur Solomonow. Ich, kenne seine politischen Ansichten. Ich bin überzeugt, dass sein Romandebüt, — Krimi, „Theater“ und der Versuch eines Gesellschaftsporträts – den klugen Leser in seinen Bann ziehen wird.

Krill Serebrennikow, Regisseur